Direct Cinema vs. Cinéma Vérité: Capturing the “truth” in Documentary Filmmaking

In the 1960s, two distinct documentary filmmaking styles emerged, both aiming to capture the truth of the human experience: Direct Cinema and Cinéma Vérité. These approaches revolutionized the genre by making use of new, more portable technology that allowed filmmakers to be less intrusive and more spontaneous. Although both styles sought authenticity, they differed significantly in philosophy, technique, and approach to capturing truth on film.

What Are Direct Cinema and Cinéma Vérité?

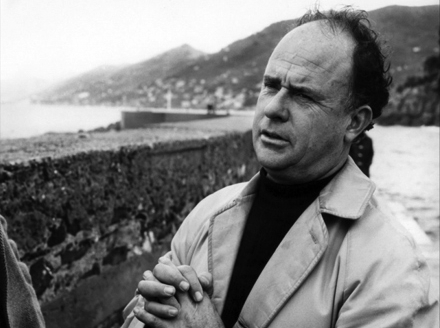

Cinéma Vérité (French for “truth cinema”) was a term coined by French filmmaker Jean Rouch, inspired by the works of Dziga Vertov, who believed that film could reveal deeper truths about reality. This style involved the filmmaker engaging with the subjects, often leading to interactions that shaped the narrative. The filmmaker wasn’t just a passive observer but an active participant, influencing how the story unfolded on camera. The goal was to reveal the raw, unfiltered experience of life, even if that meant acknowledging the filmmaker’s role in shaping that experience.

In contrast, Direct Cinema, most associated with American filmmakers like the Maysles brothers, sought to capture reality without interference. Filmmakers using this approach aimed to be as invisible as possible, allowing events to unfold without the influence of the camera or the director. The idea was to observe life as it happened, without shaping it or engaging with the subjects in any way. It promoted the notion of a neutral, objective observer capturing “truth” through pure observation.

The Role of the Filmmaker

One of the most striking differences between these two styles is the role of the filmmaker. In Cinéma Vérité, the director is part of the story, influencing the narrative by interacting with the subjects and often acknowledging the camera’s presence. Filmmakers in this tradition were not afraid to be seen and heard, and they believed that their interaction with the subjects brought out a deeper truth.

In contrast, Direct Cinema filmmakers aimed to minimize their presence, believing that true “reality” could only be captured without the filmmaker’s involvement. This approach often meant the subjects of the documentary were unaware of the film’s direction, leading to a more authentic and unmediated portrayal of their lives. Filmmakers in this tradition took a backseat to the events they were documenting.

Both styles claim to reveal the “truth” of the human experience, but they differ in how they define that truth. Cinéma Vérité holds that truth is subjective and shaped by the filmmaker’s interaction with the subjects. The filmmaker’s role is to question, provoke, and bring out moments that reveal the truth of a situation, even if it’s shaped by the filmmaker’s presence.

On the other hand, Direct Cinema posits that truth is objective and can be captured by simply observing life as it unfolds. The filmmaker is there to record, not to intervene. However, critics have pointed out that this approach, while seemingly neutral, is never truly objective because the filmmaker still makes decisions about what to film and how to frame a scene.

Key Films: A Study of Differences

To better understand the differences between these two styles, let’s take a look at two key films that exemplify the respective approaches.

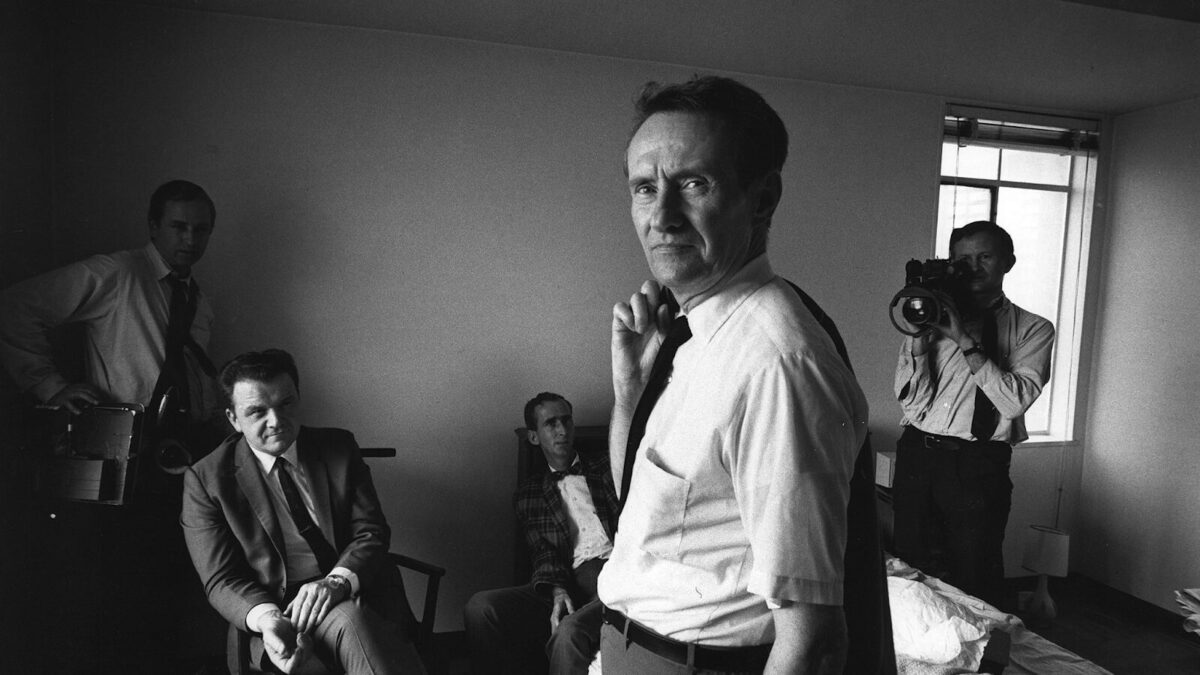

Salesman (1969) by the Maysles brothers is a prime example of Direct Cinema. The documentary follows door-to-door Bible salesmen as they try to make a living. The filmmakers take a hands-off approach, letting the salesmen speak for themselves without much interference. The camera remains unobtrusive, capturing moments of success and failure without commentary or judgment. The authenticity of the film comes from its minimal interference and the rawness of the subjects’ interactions. However, the filmmakers still make decisions—such as which moments to film and how to structure the narrative—that influence how the truth is portrayed.

In contrast, Chronicle of a Summer (1961) by Jean Rouch and Edgar Morin is a foundational film of Cinéma Vérité. This documentary captures the lives of Parisians during the summer of 1960 and is known for the active involvement of the filmmakers. Rouch and Morin engage with the subjects directly, asking probing questions and even becoming part of the narrative themselves. The filmmakers’ presence is acknowledged, and their interactions with the subjects are integral to the unfolding of the story. This approach reveals the truth of the individuals’ lives through a more subjective lens, with the filmmakers helping to draw out insights and emotions from the participants.

Criticisms and Controversies

Both Direct Cinema and Cinéma Vérité have faced criticisms over the years. Direct Cinema has been accused of being too passive, creating the illusion of an objective “truth” while still manipulating the viewer’s perception through the filmmaker’s choices of what to include or exclude. Critics have argued that by pretending to be neutral, Direct Cinema ignores the inherent subjectivity involved in filmmaking.

Cinéma Vérité, on the other hand, has been criticized for its focus on the filmmaker’s interaction with the subjects, which some feel distorts the truth. Critics, including Frederick Wiseman, have argued that Cinéma Vérité is overly concerned with the filmmaker’s role, leading to a distortion of reality. Wiseman dismissed the term entirely, claiming that it didn’t reflect his approach to documentary filmmaking.

Despite their differences, both Direct Cinema and Cinéma Vérité have had a profound impact on the documentary genre. Each approach seeks to reveal the truth, but they do so in different ways—one through passive observation and the other through active engagement. These styles reshaped the landscape of documentary filmmaking, pushing the boundaries of how truth is portrayed on screen and challenging the idea of objective reality in cinema. Today, both approaches continue to influence filmmakers, and their legacy remains central to the ongoing discussion about the ethics and authenticity of documentary filmmaking.